Application: Classifying Perovskites#

Now that we’ve covered some of the basic theory of supervised learning, let’s start applying some basic supervised learning models to a real dataset.

Perovskite Classification Dataset#

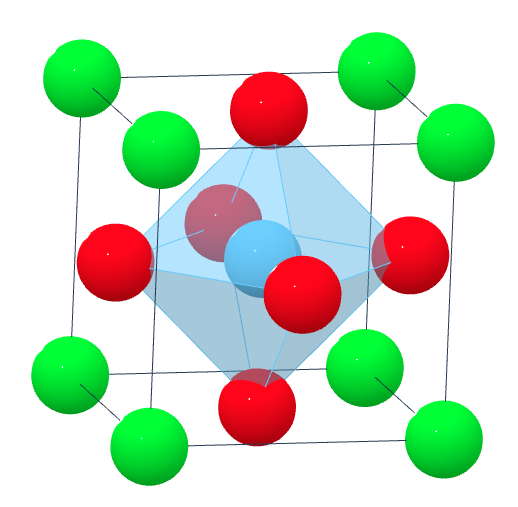

Perovskites are materials with a crystal structure of the form \(ABX_3\), where \(A\) and \(B\) are two positively charged cations and \(X\) is a negatively charged anion, usually oxygen (\(O\)). Ideal perovskites have a cubic structure, although some perovskites may attain more stable configurations with slightly perturbed structural phases, such as orthorhombic or tetragonal. Here’s an example of SrTiO\(_3\) (strontium titanate), which is most stable with a cubic structure:

We will be using the AB03 Perovskites dataset. This data was originally used in the paper Crystal structure classification in ABO3 perovskites via machine learning by Behara et al.

First, you will need to download the dataset CSV file (perovskites.csv) into the same directory as your Python notebook. You can do this by executing the following Python code in your Jupyter notebook:

import requests

CSV_URL = 'https://raw.githubusercontent.com/cburdine/materials-ml-workshop/main/MaterialsML/supervised_learning/perovskites.csv'

r = requests.get(CSV_URL)

with open('perovskites.csv', 'w') as f:

f.write(r.text)

If the code above doesn’t work, you can also download the raw CSV file here.

Once downloaded, you can load the dataset into a pandas dataframe using the following Python code:

Show code cell source

import pandas as pd

# load dataset into a pandas DataFrame:

PEROVSKITE_CSV = 'perovskites.csv'

perovskite_df = pd.read_csv(PEROVSKITE_CSV)

# show dataframe in notebook:

display(perovskite_df)

| Compound | A | B | In literature | v(A) | v(B) | r(AXII)(Å) | r(AVI)(Å) | r(BVI)(Å) | EN(A) | EN(B) | l(A-O)(Å) | l(B-O)(Å) | ΔENR | tG | τ | μ | Lowest distortion | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | Ac2O3 | Ac | Ac | False | 0 | 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 1.10 | 1.10 | 0.00000 | 0.000000 | -3.248000 | 0.707107 | - | 0.800000 | cubic |

| 1 | AcAgO3 | Ac | Ag | False | 0 | 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.95 | 1.10 | 1.93 | 0.00000 | 2.488353 | -2.565071 | 0.758259 | - | 0.678571 | orthorhombic |

| 2 | AcAlO3 | Ac | Al | False | 0 | 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.54 | 1.10 | 1.61 | 0.00000 | 1.892894 | -1.846714 | 0.918510 | - | 0.385714 | cubic |

| 3 | AcAsO3 | Ac | As | False | 0 | 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.52 | 1.10 | 2.18 | 0.00000 | 1.932227 | -1.577429 | 0.928078 | - | 0.371429 | orthorhombic |

| 4 | AcAuO3 | Ac | Au | False | 0 | 0 | 1.12 | 1.12 | 0.93 | 1.10 | 2.54 | 0.00000 | 2.313698 | -2.279786 | 0.764768 | - | 0.664286 | orthorhombic |

| ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... | ... |

| 5324 | ZrWO3 | Zr | W | False | 1 | 5 | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.62 | 1.33 | 2.36 | 2.38342 | 1.745600 | -1.572214 | 0.801621 | 5.228952455 | 0.442857 | cubic |

| 5325 | ZrYO3 | Zr | Y | False | - | - | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.90 | 1.33 | 1.22 | 2.38342 | 2.235124 | -2.489571 | 0.704032 | - | 0.642857 | cubic |

| 5326 | ZrYbO3 | Zr | Yb | False | - | - | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.95 | 1.33 | 1.10 | 2.38342 | 2.223981 | -2.626821 | 0.689053 | - | 0.678571 | orthorhombic |

| 5327 | ZrZnO3 | Zr | Zn | False | - | - | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.74 | 1.33 | 1.65 | 2.38342 | 2.096141 | -2.035750 | 0.756670 | - | 0.528571 | cubic |

| 5328 | Zr2O3 | Zr | Zr | False | - | - | 0.89 | 0.72 | 0.72 | 1.33 | 1.33 | 2.38342 | 2.043778 | -2.097821 | 0.763809 | - | 0.514286 | cubic |

5329 rows × 18 columns

Data Features#

For now, we will focus primarily on the prediction of the perovskite structure (the Lowest Distortion column). In the dataset, there are many different features given for each perovskite material. They include:

Chemical Formula (with A and B elements)

Valence of A (0-6 or unlisted): \(V(A)\)

Valence of B (0-6 or unlisted): \(V(B)\)

Radius of A at 12 coordination: \(r(A_{XII})\)

Radius of A at 6 coordination: \(r(A_{VI})\)

Radius of B at 6 coordination: \(r(B_{VI})\)

Electronegativity of A: \(EN(A)\)

Electronegativity of B: \(EN(B)\)

Bond length of A-O pair \(l(A\)-\(O)\)

Bond Length of B-O pair \(l(B\)-\(O)\)

Electronegativity difference with radius: \(\Delta ENR\)

Goldschmidt tolerance factor: \(t_G\)

New tolerance factor: \(\tau\)

Octahedral factor: \(\mu\)

In total, there are 17 distinct factors in the dataframe; however many of these features can be computed directly from other features. For example, the Goldschmidt tolarance factor is a quantity commonly used to evaluate the stability of perovskite structures. It is computed using the equation:

where \(r(A)\) and \(r(B)\) are the ionic radii of the \(A\) and \(B\) elements and \(r(\text{O})\) is the ionic radius of oxygen.

To make things a bit simpler, let’s consider only the following three factors:

Electronegativity of A: \(EN(A)\)

Electronegativity of B: \(EN(B)\)

Goldschmidt tolerance factor: \(t_G\)

We can select these features and convert them into numpy arrays using the following code:

Show code cell source

import numpy as np

# features:

a_electronegativity = np.array(perovskite_df['EN(A)'])

b_electronegativity = np.array(perovskite_df['EN(B)'])

goldschmidt_tolerance = np.array(perovskite_df['tG'])

# combine features into columns of a Nx3 numpy array:

features = np.array([

a_electronegativity,

b_electronegativity,

goldschmidt_tolerance

]).T

print('Shape of features:', features.shape)

Shape of features: (5329, 3)

Let’s also take a look at all of the distinct structures that appear in the Lowest distortion column:

Show code cell source

# dataset labels:

structures = np.array(perovskite_df['Lowest distortion'])

# reduce to distrinct values:

distinct_structures = list(set(structures))

print(distinct_structures)

['rhombohedral', 'orthorhombic', 'cubic', '-', 'tetragonal']

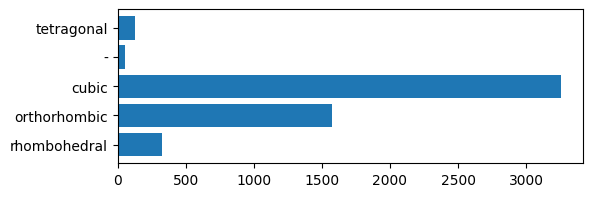

It appears that there are four different distinct phases listed in the dataset: rhombohedral, cubic, tetragonal, and orthorhombic. There are also some rows in the dataframe that do not have a phase listed (denoted by -). Let’s see how many of each phase are listed in the dataset:

Show code cell source

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

# determine how many examples of each structure are in the dataset:

bar_counts = np.array([

len(structures[structures == structure_type])

for structure_type in distinct_structures

])

# plot bar plot of counts for each type of structure:

plt.figure(figsize=(6,2))

bar_locations = np.array(range(len(distinct_structures)))

plt.barh(bar_locations, bar_counts)

plt.gca().set_yticks(bar_locations)

plt.gca().set_yticklabels(distinct_structures)

plt.show()

As expected, a majority of the perovskites have the ideal cubic structure.

Classifying Cubic versus Non-Cubic Structures:#

For simplicity, let’s first consider the problem of classifying cubic versus non-cubic structures. This is a simple binary classification task that we can solve using the binary perceptron model we learned about previously. Let’s start by removing the data entries with unknown structure (-) and assigning values of 1 to cubic structures and -1 to non-cubic structures:

Show code cell source

# determine the indices of unlabeled data:

clean_data_idxs = (structures != '-')

# remove unlabeled data from features:

clean_features = features[clean_data_idxs]

clean_structures = structures[clean_data_idxs]

# assign binary classifier labels +1/-1 for cubic/non-cubic:

binary_classifier_labels = np.array([

1 if struct == 'cubic' else -1

for struct in structures

])

print('Features shape:', clean_features.shape)

print('Binary classifier labels shape:', binary_classifier_labels.shape)

Features shape: (5276, 3)

Binary classifier labels shape: (5329,)

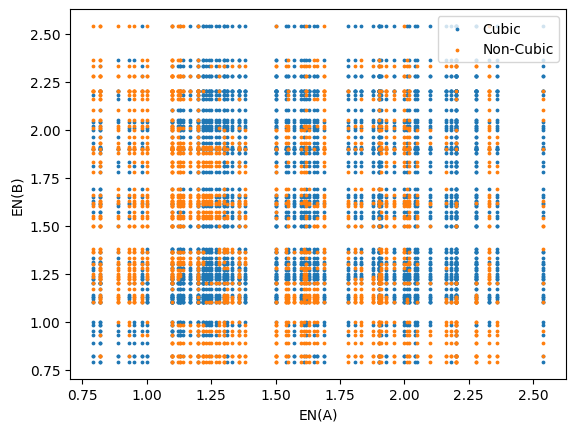

Let’s visualize what the cubic versus non-cubic data looks like with respect to electronegativity (A and B):

Show code cell source

# separate out cubic and non-cubic data:

cubic_data = features[binary_classifier_labels == 1]

noncubic_data = features[binary_classifier_labels == -1]

# plot EN(A), EN(B) for cubic and non-cubic data:

plt.figure()

plt.scatter(cubic_data[:,0], cubic_data[:,1], s=3.0, label='Cubic')

plt.scatter(noncubic_data[:,0], noncubic_data[:,1],s=3.0, label='Non-Cubic')

plt.xlabel('EN(A)')

plt.ylabel('EN(B)')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

Since the electronegativity generally increases with the group and decreases with the period of elements on the periodic table, it serves as a good numerical quantity to associate with each element. This is why we observe a grid-like distribution of the data. From glancing at the distribution of cubic versus non-cubic materials, it appears that there is no immediately identifiable trend.

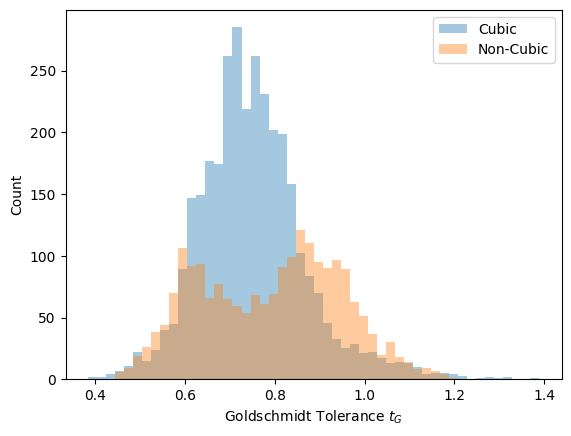

Let’ also look at how the cubic and non-cubic structures are distributed with respect to the Goldschmidt tolerance factor \(t_G\):

Show code cell source

# define the histogram "bins" used to visualize the t_G distribution:

hist_bins = np.linspace(np.min(goldschmidt_tolerance),

np.max(goldschmidt_tolerance), 51)

# plot histograms of cubic and noncubic data with respect to t_G:

plt.figure()

plt.hist(cubic_data[:,2], bins=hist_bins, alpha=0.4, label='Cubic')

plt.hist(noncubic_data[:,2], bins=hist_bins, alpha=0.4, label='Non-Cubic')

plt.xlabel('Goldschmidt Tolerance $t_G$')

plt.ylabel('Count')

plt.legend()

plt.show()

We see that a majority of the cubic structures are distributed within the range of \(t_G = 0.7\) to \(t_G = 0.9\). According to the literature, perovskites with \(t_G\) in the range of \(0.9\) to \(1.0\) are generally predicted to be in the cubic phase, which appears to be inconsistent with our data. Taking note of this discrepancy, we will proceed with preparing our data. First, we will split the data into training, validation, and test sets. This can be done with the sklearn.model_selection.train_test_split function. We will also standardize our data using sklearn.preprocessing.StandardScaler:

Show code cell source

from sklearn.model_selection import train_test_split

from sklearn.preprocessing import StandardScaler

# split train and non-training data 80% and 20%:

x_train, x_nontrain, y_train, y_nontrain = train_test_split(

features, binary_classifier_labels, train_size=0.8)

# further split non-training data into validation and test data:

x_val, x_test, y_val, y_test = train_test_split(

x_nontrain, y_nontrain, test_size=0.5)

# Determine the standardizing transformation:

x_scaler = StandardScaler()

x_scaler.fit(x_train)

# transform x -> z (standardize x data):

z_train = x_scaler.transform(x_train)

z_val = x_scaler.transform(x_val)

z_test = x_scaler.transform(x_test)

print('Shape of z_train:', z_train.shape)

print('Shape of z_val:', z_val.shape)

print('Shape of z_test:',z_test.shape)

Shape of z_train: (4263, 3)

Shape of z_val: (533, 3)

Shape of z_test: (533, 3)

The Perceptron (Linear Classification) Model#

One of the simplest two-class classification models is a linear classifier model, historically referred to as a Perceptron model. For a standardized feature vector \(\mathbf{z}\) with \(N\) features, a linear classifier model \(f(\mathbf{z})\) makes “1” and “-1” class predictions according to the equation:

where \(w_0, w_1, ..., w_N\) are learned weights of the model. In this case, a prediction of \(1\) corresponds to the cubic class, and \(-1\) corresponds to the non-cubic class. We can fit a Perceptron model to the data using the sklearn.linear_model.Perceptron class.

Show code cell source

from sklearn.linear_model import Perceptron

# fit a linear perceptron model to training set:

perceptron = Perceptron()

perceptron.fit(z_train, y_train)

# evaluate the model on the training and validation set:

train_accuracy = perceptron.score(z_train, y_train)

val_accuracy = perceptron.score(z_val, y_val)

# print the accuracy of the model:

print('training set accuracy: ', train_accuracy)

print('validation set accuracy:', val_accuracy)

training set accuracy: 0.4309171944639925

validation set accuracy: 0.42964352720450283

From our visualization of the cubic vs. non-cubic perovskites, we saw that the separation between these two classes is very non-linear, so we expect both the training set and validation accuracy to be low. Nonetheless, we do see that the validation accuracy is greater than \(0.6\), which appears to be statistically significant improvement upon random guessing.

The Nearest Neighbor Model#

Before trying other models, it may help to see what kind of accuracy can be attained by a nearest neighbor classification model. As the name suggests, a nearest neighbor classification model predicts the class of an unseen standardized data point \(\mathbf{z}\) to be the majority class in the set of \(k\) standardized data points in the training set that are nearest to \(\mathbf{z}\). By “nearest”, we refer to the point with the smallest Euclidean distance:

Typically, an odd number of neighbors \(k\) is used. While \(k\)-nearest neighbor models tend to give good results, they may not be suitable for large datasets or datasets with many features, as searching for the nearest neighbors in a dataset may be computationally expensive.

Show code cell source

from sklearn.neighbors import KNeighborsClassifier

# fit a k-nearest neighbor classifier (k=7 in this case):

knc = KNeighborsClassifier(n_neighbors=7)

knc.fit(z_train, y_train)

# evaluate the model on the training and validation set:

train_accuracy = knc.score(z_train, y_train)

val_accuracy = knc.score(z_val, y_val)

# print the accuracy of the model:

print('training set accuracy: ', train_accuracy)

print('validation set accuracy:', val_accuracy)

training set accuracy: 0.8179685667370397

validation set accuracy: 0.7729831144465291

An important property of nearest neighbor models is that no learning actually takes place with the training data; rather, the model is the training data. This can be viewed as either a criticism or a strength of the model, depending on whether the goal is to just to make accurate predictions or to find a simple and interpretable model that still makes accurate predictions. Often the latter kind of model is preferred over the former, so nearest neighbor models are not often the best choice for supervised tasks. However, these models can be useful in establishing a baseline accuracy that one can attempt to match with models that have less complexity.

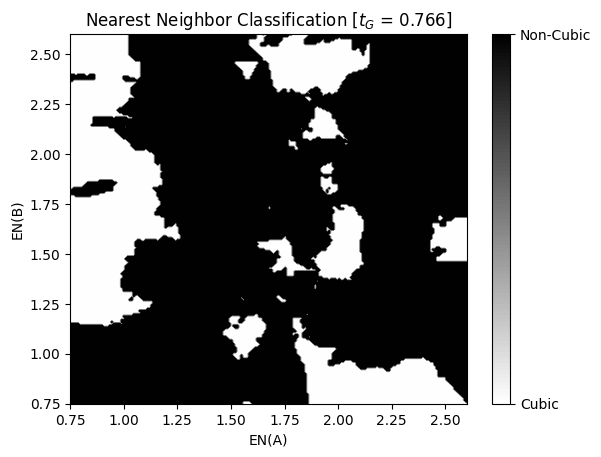

As expected, the nearest neighbor model is much more accurate than the Perceptron model we tried earlier. This is because it is capable of capturing some of the non-linearities of classes, especially with regards to the electronegativity of the \(A\) and \(B\) atoms. We can write some Python code to visualize this as follows:

Show code cell source

en_range = (0.75, 2.6)

eval_tG = np.mean(x_train[:,2])

mesh_size = 200

a_mesh, b_mesh = np.meshgrid(

np.linspace(en_range[0],en_range[1], mesh_size),

np.linspace(en_range[0],en_range[1], mesh_size))

mesh_features = np.array([

a_mesh.flatten(),

b_mesh.flatten(),

eval_tG*np.ones_like(a_mesh.flatten())

]).T

z_mesh_features = x_scaler.transform(mesh_features)

predictions = knc.predict(z_mesh_features)

predictions_mesh = predictions.reshape(a_mesh.shape)

plt.figure()

surf = plt.contourf(a_mesh, b_mesh, predictions_mesh, cmap='binary', levels=100)

cbar = plt.colorbar(surf)

cbar.ax.set_yticks([-1,1])

cbar.ax.set_yticklabels(['Cubic','Non-Cubic'])

plt.xlabel('EN(A)')

plt.ylabel('EN(B)')

plt.title(r'Nearest Neighbor Classification [$t_G$ = ' + f'{eval_tG:.3f}]')

plt.show()

Now that we have established a baseline accuracy using the nearest neighbor model, let’s try to exceed this baseline accuracy with a more complex model.

Decision Tree Classifier#

Next, let’s try a model that is slightly more complex than the perceptron classifier: a Decision Tree Classifier. As the name suggests, a decision tree classifier works by constructing a decision tree based on individual features. Decision trees are especially well-suited to datasets with independent features that tend to exist in many small clusters. Since the distribution of cubic and non-cubic perovskites with respect to electronegativity is grid-like and contains many small clusters, we may obtain good results with a decision tree. To fit a decision tree to the data, we will use the sklearn.tree.DecisionTreeClassifier model. Since most of the sklearn models conform to the same interface for fitting and evaluating model accuracy, we only need to make a few changes to our code to try out this model:

Show code cell source

from sklearn.tree import DecisionTreeClassifier

# fit a decision tree model to the data:

dtree = DecisionTreeClassifier(max_depth=10)

dtree.fit(z_train, y_train)

# evaluate the model on the training and validation set:

train_accuracy = dtree.score(z_train, y_train)

val_accuracy = dtree.score(z_val, y_val)

# print the accuracy of the model:

print('training set accuracy: ', train_accuracy)

print('validation set accuracy:', val_accuracy)

training set accuracy: 0.868402533427164

validation set accuracy: 0.776735459662289

Comparing the validation error of the decision tree classifier with the nearest neighbor model from before, we see that the decision tree classifier performs slightly better.

Exercises#

Exercise 1: Histogram Gradient Boosting Machine

In the paper that produced this dataset, the model that yielded the best accuracy was the Light Gradient Boosting Machine (LGBM), developed by Microsoft Research. A similar gradient boosting model is implemented in the sklearn package as sklearn.ensemble.HistGradientBoostingClassifier.

Fit this model to the same data as the other models. Try to adjust the learning_rate and max_leaf_nodes to maximize the validation set accuracy. Estimate the final accuracy of the model by evaluating it on the test set.

Solutions#

Exercise 1: Histogram Gradient Boosting Machine#

Show code cell content

from sklearn.ensemble import HistGradientBoostingClassifier

# fit a histogram gradient boosting model classifier:

hgbm = HistGradientBoostingClassifier(

max_leaf_nodes=180,

learning_rate=0.08,

)

hgbm.fit(z_train, y_train)

# evaluate the model on the training and validation set:

train_accuracy = hgbm.score(z_train, y_train)

val_accuracy = hgbm.score(z_val, y_val)

test_accuracy = hgbm.score(z_test, y_test)

# print the accuracy of the model:

print('training set accuracy: ', train_accuracy)

print('validation set accuracy:', val_accuracy)

print('test set accuracy:', test_accuracy)

training set accuracy: 0.9678630072718742

validation set accuracy: 0.8180112570356473

test set accuracy: 0.7917448405253283